Middle school math – teaching notes – 1

I have never been great at math. Even as I was preparing for my engineering entrance exams, Math was my weakest subject – in my board exams, I scored the least in Math.

Later in life, as I did my engineering, as I taught both math and engineering, and as I used more and more math, I found it fascinating.

The reason I was bad at math is rather obvious to everyone who studied it while growing up – bad design of the math programs and bad teaching. But which specific aspect of bad design and teaching impacted me most negatively?

I will then have to pick the way different aspects and techniques were presented, without any focus on the underlying connections between them. Algebra is presented as a mystery science by itself. Calculus does not start with the problem of finding the area under the curve. I got to hear of fluxions late life. Pi is presented as an empirical constant related to the circle, infinite series just appear out of nowhere and many many more beautiful connections that would bring out the beauty of high school math, are totally ignored.

At farm hill, when I started teaching math about a couple of years back, I I decided to see if these connections can be highlighted and I am glad to report that my three students like the approach.

One of the ways I found to make this work is to ask myself, “how did the first person who thought of this, go about doing it?” And modify it to suit the context. When I took this approach, I saw how much of the beauty of math we have destroyed in adopting it to be taught easily (easy for the teahcers) in small chunks.

That’s enough of the rant. Let me present a couple of thoughts on how one can go about this, in middle school (Grades 6 to 8). Oh, by the way, I was also kind of pushed to this way because my students hated math, to start with.

My go to method is guided discovery, sessions are interactive, and interactions are socratic. So whenever I say show or establish or lead to, I mean it can be done through an interactive discussion and not as a capsule pushed down the throat.

Also, please note this is written as a quick note for fellow teaching learning enthusiasts. Treat the writing below accordingly.

—-–————–

Introduction

We start with geometry first. Start with a point, line as a collection of points, plane as a collection of lines, solids as collections of planes.

Then, since we start with plane geometry, we examine the way two lines can be arranged in a plane. Quick to see that either they are parallel or they intersect.

From intersecting lines, establish the idea of an angle as the rotational distance between lines, the idea of a straight angle, and the idea that opposite angles are equal. Park parallel lines for now.

Now, consider bringing in another line into this plane. Again, quickly see that either the lines are

(a) all parallel to each other

(b) two are parallel and third intersects as a transversal

(c) all intersect at the same point or

(d) two lines intersect at a time to make a triangle

Park a and c above for now.

Choosing b, and using the ideas from two intersecting lines, establish the bunch of ideas around the angles formed – corresponding angles are equal, internal angles on the same side add to a straight angle, opposite internal angles are equal etc.

Now, choose case d. The triangle is the first closed figure that can be formed on a plane, using straight lines. Have students draw different kinds of triangles, cut them out and arrange the angles together to make a straight angle. Let them experiment with triangles of various sizes and shapes. Let them see that however they make the triangle, the angles can be arranged along a straight line.

Now, let’s ask if this would be true for all the triangles. Here, we can discuss the ideas of empirical results and mathematical proof. Yes, we have seen that the 15-20 triangles you made all have angles that can be arranged along a straight line. Based on this, are we really allowed to conclude this will be the same for all triangles? May be we cannot. May be there will a triangle whose angles are not along a straight line. How do we know for sure?

At this point, if you have the time or energy, talk about how we do this in”science”. For example, when do we decide a medicine is a good cure for cold? We conduct an experiment and if enough number of people get cured, we recommend it as a cure. Obviously that kind of logic does not work in mathematics. Why?

Now, illustrate a math proof. Construct a fourth line parallel to any one of the lines and use the results from two intersecting lines case and two parallel lines and a transversal case above to show that the angles of any triangle, can be arranged along a straight line.

Talk about how this remains true for all traingles.

Strand 1.1 angles in polygons

In this strand, we continue to focus on the angles in closed figures. Now that we have shown the angles in a triangle can be arranged along a straight line, what can we say about angles in a quadrilateral, pentagon, hexagon and so on?

Draw a quadrilateral and show it can be divided into two traingles. Draw polygons with increasing number of sides and show that each time one more side is added, we add the angles of a triangle to the figure. Hint: drawing cyclic polygons makes this easy to show.

Branch 1:

Make a table of number of sides of a polygon and the number of staight angles in it. 3 sides will be one straight angle and there after, for every new side, an additional straight angle is added. You can treat this as a sequence and write down the general formula that can generate the sequence.

Branch 2:

Go back to the cyclic polygons and show that a polygon of n sides can be didived into n triangles, with the vertices of all the triangle at any point inside the polygon. These triangles bring in n straight angles. However, this also includes the two straight angles made at the point where the vertices are meeting. These two straight angles are not part of the intenral angles of the polygon, and need to be subtracted. We get the same formula as in branch 2 again.

Point out that the two straight angles at the center remain the same for any polygon, irrespective of the number of triangles.

Spend sometime distinguishing the approaches between branch 1 above and here. Which of these is mathematically more robust?

Strand 1.2 Areas

Start with a rectangle, the next closed figure. Show that multiplying the two sides is the same as counting the number of unit squares covered by the rectangle.

Now, go back to the triangle and ask how to find the area. Draw a right angled triangle and show that it is half of a rectangle. Draw any triangle, and show that a rectangle can always be constructed such that the area of the rectangle is double the area of the triangle. And so, get the formula for the area of the triangle.

Continue to show that the area of any polygon can be calculated by dividing into triangles.

Continue to different types of quadrilaterals like squares, parallelograms, trapeziums, kites etc., extending the ideas of area. Derive relevant formulae.

——-++++++

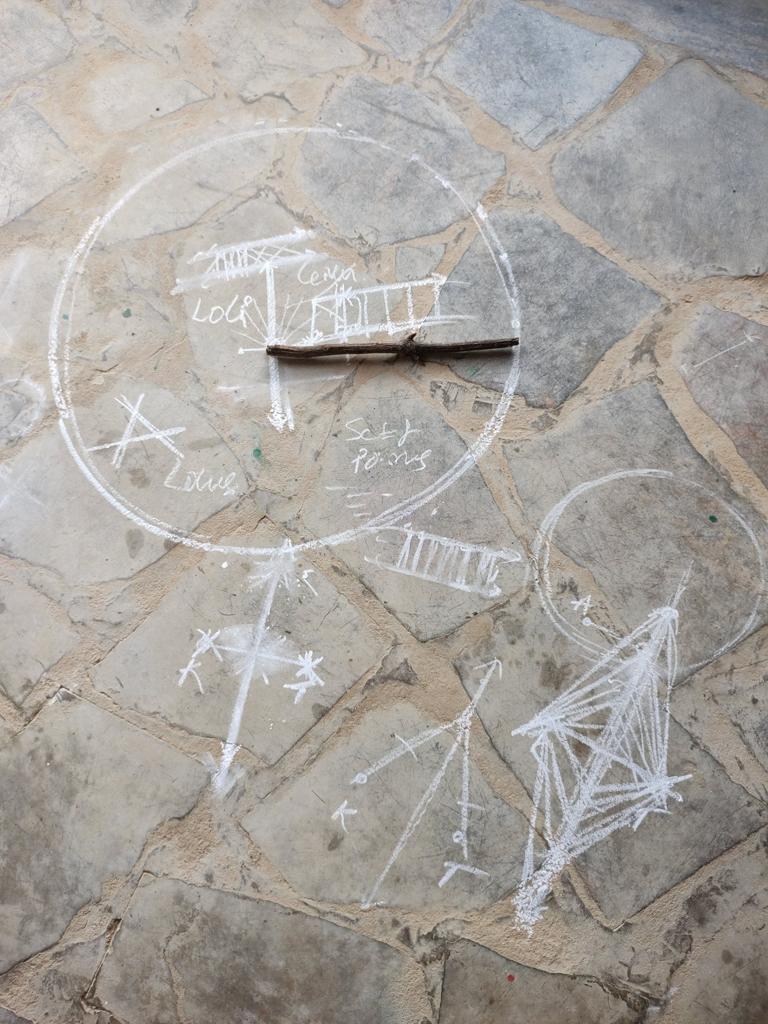

Strand 2 loci – parallel lines, perpendicular bisectors, circle

Parallel lines and locus

Start with parallel lines. How do we know two lines are parallel? Lead to the idea that the distance between corresponding points on the lines has to stay the same.

In other words, if we pick up any point on a line and move it a fixed distance in any direction, and do the same for all points, we get a new line that is parallel to the original one.

Introduce the idea of points that move around following a rule. The above is an example.

Perpendicular bisector and locus

Start with another thought experiment. Let us say, two students are standing in a field. A third student has to stand in such a way that she is at an equal distance between them. Once she finds a point, ask if she can move, while keeping her distance from both the other students same. Slowly lead to the idea that there is an entire line on which she can stand, while following the equal distance rule.

Now ask what is the angle between the line connecting the two students and the line on which the third student can move. Slowly lead to it being half of the straight angle. Now introduce the idea of the perpendicular and extend it to show that the line the third student moved on is the perpendicular bisector of the line segment connecting the two students.

This is the second example of a locus.

Circle and locus

Circle and locus

Ask the students to draw a circle free hand. Discuss whether what they have drawn is really a circle and how they would improve the “roundness”. Suggest the idea of drawing a cross inside the circle to be able to draw a more round circle.

How can we improve the roundness of the circle further? By drawing more lines passing through the intersection of the cross. Let them draw and ask about the length of the lines drawn to make the circle more of a circle.

Arrive at the idea that the lines are all of the same length. Introduce the idea that the points on a circle are at a fixed distance from the point of intersection of all the lines drawn to make it more round.

Introduce the idea of the center and the radius/diameter. Discuss how a compass produces a circle. Talk about how construction workers draw circles using a rope tied to a fixed point.

This is the third example of locus.

Using the idea of locus to draw perpendicular bisector

Now connect the following two ideas.

1. Points on the perpendicular bisector of a line segment are at equal distances from the end points.

2. Points on a circle are equidistant from the center.

Slowly show that when circles with the same radius are drawn at the end points of a line segment, and they intersect, the two points of intersection of the circles are at the same distance from both the end points. So, these points are on the perpendicular bisector. Connecting these points gives us the perpendicular bisector of the line segment.

A few ideas to emphasize:

Drawing the circle is just to identify the points that are equidistant from the two end points. The usual method of drawing two arcs on either side of the line segment is the same as this.

The points need not be on either side of the line segment though. We can take a radius, draw two arcs with the end points of the line segment as centers that bisect on one side of the line segment, then change the radius and draw two more arcs that bisect on the same side. We still have two points on the perpendicular bisector. This will reinforce the idea of the properties of the points and take the focus away from the rote method.

Once students understand the idea of using arcs of a circle to identify equidistant points, a number of geometrical constructions become easy to figure out.

“Practical geometry” chapters in NCERT textbooks for grades 7 and 8, where students learn to draw triangles and quadrilaterals are based on this idea.

—–+++++++++

Strand 3 Pythogorian triples and Pythagoras theorem

Start with asking how would you build a perfect square in the field, as it requires creating a right angle. Ideas from the perpendicular bisector will come through here.

Is drawing a perpendicular bisector feasible everywhere? Go on to talk about pyramids where you need to ensure a right angle at every corner as you go up the pyramid. Also, is there an easier way to do this?

Go back to the perpendicular bisector and show that there are two right angles in the figure formed.

Then show that a tringle once formed, the sides can always be reassembled in to the same triangle. This is not true for squares or rectangles.

Therefore, once you build a right angle triangle, and note down the sides, you will be always be able to reassemble the triangle anywhere.

Would it help if the sides of this right angle triangle we build are whole numbers? Yes, since whole number units are easier to measure and replicate.

Encourage the students to experiment with right angle triangles of different sides, till they find three while numbers that form the sides of the triangle.

Hint: they can draw perpendicular bisector to one line segment, mark units on the two sides, and join the points in different ways. Using a graph sheet to this is easier still.

They will find 3, 4 and 5. Introduce the idea of pythogorean triplets. Show them how masons use this in the field to make right angles.

Introduce triangle numbers and square numbers. Show these as number series. Park this idea for further use when we come to dealing with number series.

Show that pythogorean triples are formed when two squares are added to make another square.

Lead to the formal statement of pythogoras theorem.

——++++++++++++

By now, we have covered triangles, rectangles, squares, other polygons, their sum of angles and areas. We have covered loci and circles. We have covered basic ideas of geometric constructions. Right angled triangles, pythogorean triples and pythogoras theorem are covered.

Now, let’s introduce the idea of perimeter. Easy enough to write formulae.

Strand 4 circle area and perimeter

Approaching a new problem, using approximations, noticing patterns, the way one takes leaps of imagination – all of these can illustrated in this.

Draw squares around..establish outer limits.

Area is in square terms, perimeter is unit terms. Radius is the defining parameter of a circle. So formulas will be in terms of radius. So, intuitively it can be seen that the perimeter will be a linear function of the radius and areas will be a linear function of the radius square.

Empirical measures – draw circles of different radii on graph sheets. Find their perimeters using compass or thread. Find area by counting the squares.

Show there is a linear relationship between radius and perimeter and a linear relationship betwee radius square and area, using the empirical measures.

Show the more robust proof of the relationship between area and perimeter by cutting the circle up into sectors.

Calculate the ratio of perimeter and radius, and area and radius, empirically.

Archimedes – Show how an inscribed regular hexagon gives a better measure of the approximate area and perimeter. Show that a hexagon gives us a relationship between radius and the side of the inscribed polygon.

How about we draw bigger circles, more sided polygons and measure the area and perimeter? This was the preferred method to calculate constants in the area and perimeter functions.

Introduce Li hiu method. Uses right angle triangles and pythogoras theorem to calculate the area of a polygon that has double the sides of the hexagon, and so on.

Calculate the value of Pi.

Strand 5 – yet to be expanded

Newton and Pi values. Binomial expansions, infinite series, areas under the curve. Integration. Differentiation.