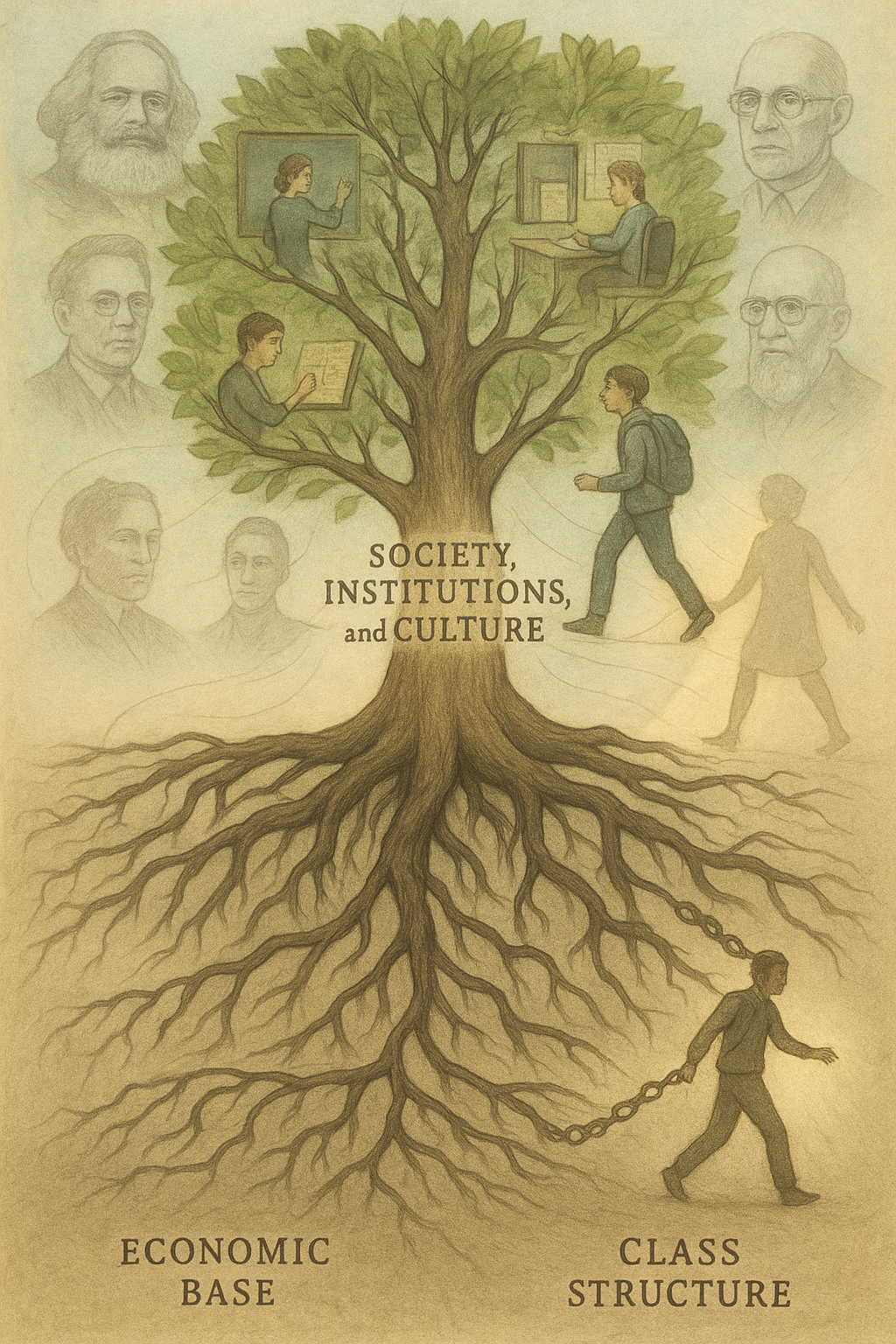

Social and Cultural Reproduction and Resistance - Marx to Giroux

1. Karl Marx: The Economic Foundation of Reproduction

Model:

Marx’s analysis is the starting point for all later theories. He argued that the economic “base” (relations and forces of production) determines the “superstructure” (institutions, culture, law, ideology). The ruling class maintains its dominance by controlling the means of production, and the superstructure serves to legitimize and reproduce class relations.

Resistance:

Marx saw resistance as collective, class-based revolution. The working class, through developing class consciousness, could overthrow capitalism. However, his model has been critiqued for economic determinism and for underestimating the role of culture and ideology.

2. Antonio Gramsci: Hegemony, Consent, and Cultural Struggle

Builds on Marx:

Gramsci extended Marx’s theory by emphasizing the importance of culture, ideology, and civil society. He introduced the concept of hegemony—the process by which the ruling class maintains dominance not just through coercion but by securing the consent of subordinate groups.

“Hegemony is not a static condition but a dynamic process. It must be constantly renegotiated and maintained, as subordinate groups can challenge or resist the dominant ideology. This makes hegemony a site of struggle, where different social forces compete to shape cultural and political life.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Antonio Gramsci)

Resistance:

Gramsci distinguished between “war of maneuver” (direct confrontation) and “war of position” (strategic, cultural struggle). He highlighted the need for counter-hegemonic alliances and “organic intellectuals.”

4. Bowles & Gintis: Correspondence Theory and Structural Reproduction

Build on Marx and Jackson:

In Schooling in Capitalist America (1976), Bowles and Gintis formalized the correspondence principle: schools mirror the hierarchical structure of the workplace, and the hidden curriculum prepares students for their future roles in the labor market.

“The practices and ideologies prevalent in American schools reproduced the social division of labor engendered by the United States capitalist economy… the socialization function of schooling prepares individuals for accepting their role in the hierarchical structure of the workplace…” (Bowles & Gintis, 1999).

Resistance:

They acknowledge class conflict and resistance, but their structural focus is often critiqued for underplaying agency.

5. Pierre Bourdieu: Habitus, Cultural Capital, and Symbolic Violence

Builds on Marx, Gramsci, Bowles & Gintis, and Jackson:

Bourdieu’s model centers on habitus (internalized dispositions), cultural capital (privileged knowledge, language, and tastes), and field (structured social arenas). He shows how schools “legitimize the transmission of cultural capital and the reproduction of social structure by treating the transmission of inherited cultural capital as if it were the product of individual effort and merit” (Bourdieu & Passeron, 1977, p. 9).

“The habitus, a product of history, produces individual and collective practices… in accordance with the schemes generated by history.” (Bourdieu, 1977, p. 82)

Resistance:

Bourdieu sees resistance as possible but deeply constrained by the internalization of social structures.

6. Paulo Freire: Praxis, Conscientization, and Liberation

Builds on Marx, Gramsci, and adds a dialogical, participatory focus:

Freire’s critical pedagogy critiques the “banking model” of education, where students passively receive knowledge. He advocates for dialogical, problem-posing education that fosters conscientization—the development of critical consciousness.

“Freire endorses students’ ability to think critically about their education situation… Realizing one’s consciousness (‘conscientization’, ‘conscientização’) is then a needed first step of ‘praxis’, which is defined as the power and know-how to take action against oppression while stressing the importance of liberating education.” (Freire, 2016, p. 73)

Resistance:

For Freire, resistance is the very purpose of education: “Freire’s vision for critical pedagogy was rooted in liberating individuals from social and cultural dominance… encouraging marginalized, illiterate communities to break free from a culture of silence.”

7. Michael Apple: Contradiction, Agency, and Schools as Sites of Struggle

Builds on Marx, Gramsci, Bowles & Gintis, Bourdieu, Jackson, and Freire:

Apple sees schools as institutions that reproduce social inequalities through both the formal and hidden curriculum, but he emphasizes contradiction, agency, and struggle:

“Social reproduction is by its nature a contradictory process, not something that simply happens without a struggle.” (Apple, 1995, p. 84)

He highlights the relative autonomy of students and teachers and the potential for resistance and counter-hegemonic alliances.

8. Michel Foucault: Power/Knowledge, Discipline, and Subject Formation

Builds alongside and diverges from Marxist tradition:

Foucault shifts the analysis from class and ideology to the microphysics of power—how power operates through knowledge, institutions, and practices to produce subjects. Power is dispersed, relational, and productive.

“We should not try to look for the center of power… but should rather construct a ‘microphysics of power’ that focuses on the multitude of loci of power spread throughout a society: families, workplaces, everyday practices, and marginal institutions.” (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Michel Foucault)

Resistance:

For Foucault, “where there is power, there is resistance” (Foucault, 1978). Resistance is local, fragmented, and embedded within power relations.

9. Henry Giroux: Critical Pedagogy, Agency, and Democratic Possibility

Builds on Marx, Gramsci, Bourdieu, Freire, Apple, and Foucault:

Giroux critiques traditional reproduction theories for overemphasizing structure and neglecting agency. He integrates Marxism, cultural studies, and critical theory, arguing that education can be a site for critical consciousness and transformative action.

“Giroux (1983) contended the theory by arguing that it prioritized structure and neglected human agency in its analysis of the reproduction of inequality.”

He champions teachers and students as transformative intellectuals who can challenge domination through critical pedagogy.

Comparative Table (Reflecting Intellectual Development)

| Theorist | Model of Reproduction | Mechanism(s) | Resistance: Possibility & Scope | Limitations of Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marx | Economic/class-based | Base-superstructure, class relations | Collective revolution, class struggle | Economic determinism; underplays culture |

| Gramsci | Hegemony/consent | Cultural/ideological leadership, civil society | “War of position,” counter-hegemonic alliances | Requires long-term cultural work |

| Jackson | Hidden curriculum | School routines, socialization | Awareness as basis for reform or resistance | Subtle, often unrecognized by participants |

| Bowles & Gintis | Correspondence theory | Hidden curriculum, school-work parallels | Class conflict, uneven development | Structural focus; limited agency |

| Bourdieu | Habitus, cultural capital | Symbolic violence, everyday practice | Limited, via agency, “slippage,” collective action | Habitus limits imagination; deep internalization |

| Freire | Praxis, conscientization | Dialogic education, problem-posing | Collective liberation, critical consciousness | Requires ongoing praxis and dialogic engagement |

| Apple | Contradiction, agency | Hidden curriculum, policy, school culture | Everyday acts, collective alliances | Shaped/limited by structure and policy |

| Foucault | Power/knowledge, discipline | Microphysics of power, normalization | Local, fragmented, ever-present | Diffuse, not necessarily transformative |

| Giroux | Critical pedagogy, agency | Cultural politics, teacher/student agency | Transformative pedagogy, critical consciousness | Requires critical agency and institutional support |

Conclusion

Theories of social and cultural reproduction have evolved through a rich intellectual genealogy. Marx laid the economic foundation, which Gramsci expanded into the cultural and ideological realm. Jackson empirically revealed the hidden curriculum, which Bowles & Gintis theorized as a mechanism for labor reproduction. Bourdieu deepened the analysis with habitus and cultural capital, while Freire and later Giroux and Apple foregrounded agency, critical consciousness, and the transformative potential of education. Foucault shifted the lens to the dispersed, productive nature of power and the formation of subjectivity. Each thinker built upon, critiqued, or reimagined the insights of their predecessors, resulting in a nuanced understanding of how domination is maintained—and how it might be contested—within education and society.

References:

Marx, K. (1867). Capital

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks

Jackson, P. (1968). Life in Classrooms

Bowles, S., & Gintis, H. (1976). Schooling in Capitalist America

Bourdieu, P. & Passeron, J.-C. (1977). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed

Apple, M. W. (1995). Education and Power (2nd ed.)

Foucault, M. (1978). The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1

Giroux, H. (1983). Theory and Resistance in Education

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Antonio Gramsci; Michel Foucault